Baby steps: Kasich budget improves childcare, but not nearly enough

February 27, 2015

Baby steps: Kasich budget improves childcare, but not nearly enough

February 27, 2015

Contact: Wendy Patton, 614-221-4505

Support also helps employers maintain stability

Gov. John Kasich’s budget proposal would slightly improve Ohio’s childcare assistance program, which has some of the most stringent eligibility standards in the nation. Much more needs to be done to support low-wage families and help employers maintain a reliable, skilled workforce.

Gov. John Kasich’s budget proposal would slightly improve Ohio’s childcare assistance program, which has some of the most stringent eligibility standards in the nation. Much more needs to be done to support low-wage families and help employers maintain a reliable, skilled workforce.

This brief explains the problems in public childcare: the cliff, the cracks and the canyon in which most families get stuck. It outlines the improvements proposed in the 2016-17 executive budget and recommends ways to fix the remaining deficiencies of Ohio’s program, which will continue to trap parents in low-wage jobs, even with the budget proposals.

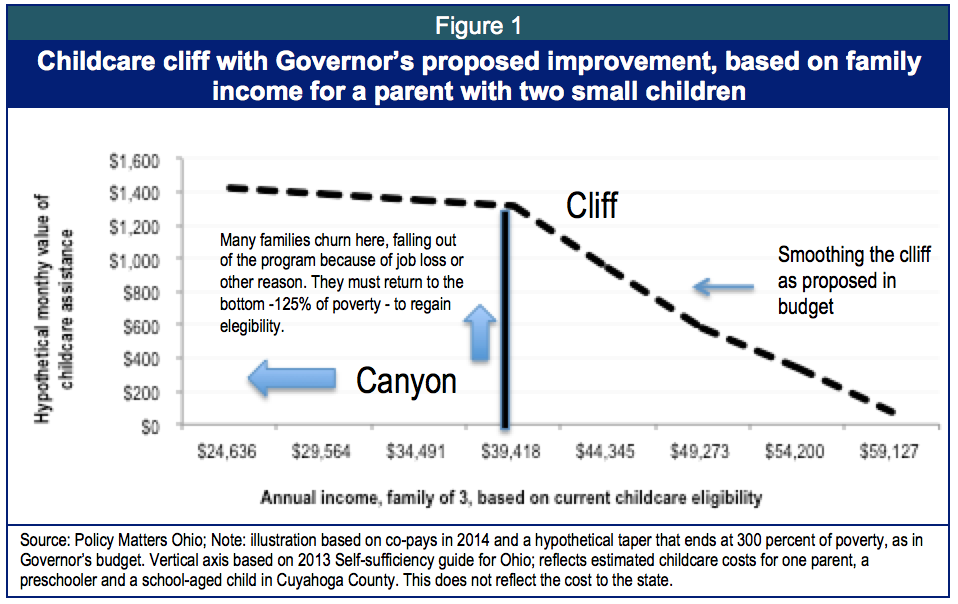

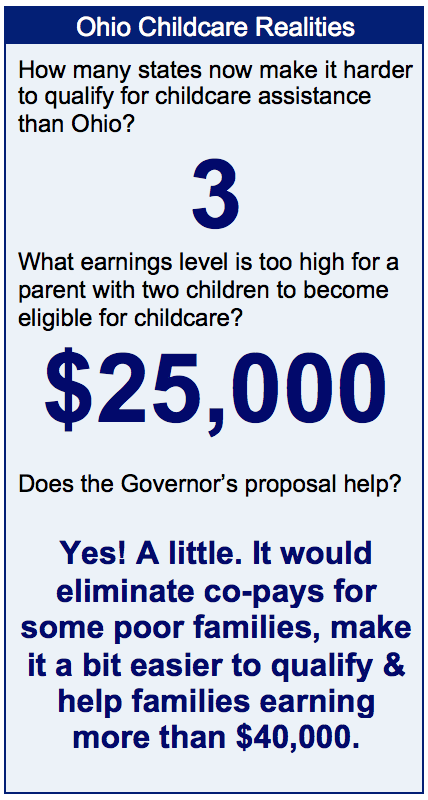

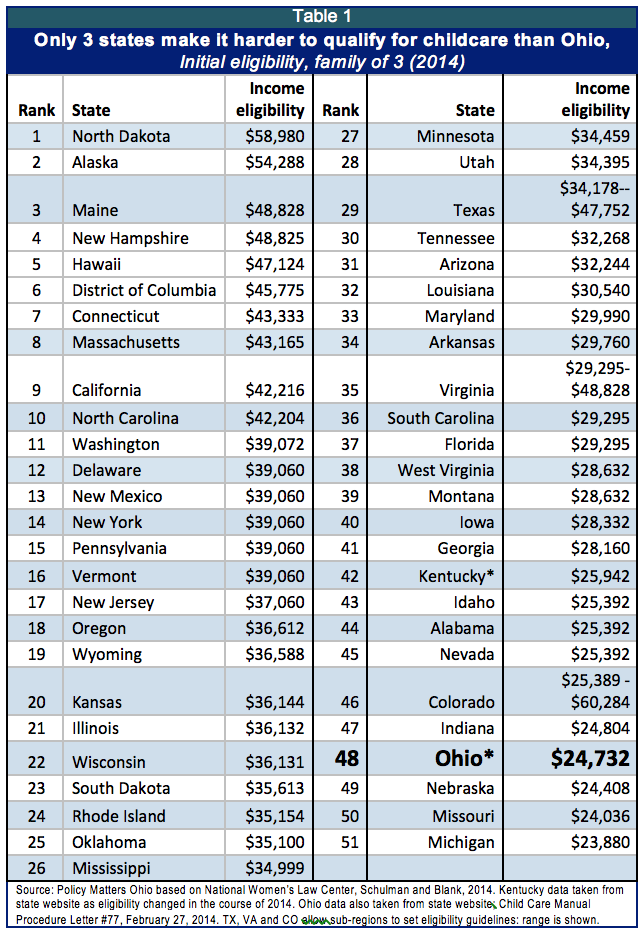

What is the cliff?Ohio has the 48th lowest level of initial eligibility at about $24,732 or 125 percent of poverty in 2014.[1] Only three states make it harder. Families can stay in the program as income rises to 200 percent of poverty, but only if they do not have an interruption in enrollment. With an interruption, they must start again at the bottom - 125 percent of poverty - to get assistance.

The childcare cliff appears when a parent gets a raise that pushes her income above the ceiling for eligibility in public childcare assistance, but not enough of a raise to pay for the steep cost of childcare.

An Ohio family of three (a parent with two young children) can enter the program with income of $24,732 or less. The family remains in the program until income hits the ceiling for eligibility at $39,576 (200 percent of poverty in 2014).[2] For this family, public childcare assistance keeps the cost of childcare to less than 9 percent of total income, which is about $300 a month ($3,561 a year) at the edge of the cliff.

The real cost of childcare is much, much higher, taking 40 percent of family income for a single parent with an infant and 33 percent for a single parent with one preschooler.[3] A parent with two young children faces extremely high costs. According to the Ohio Community Action Agencies’ “Self-Sufficiency Guide for Ohio Counties for 2013,” the cost of childcare for a preschooler and school-aged child in Cuyahoga County is $1,602 a month[4] or $19,224 a year – almost half of family income at 200 percent of poverty ($39,576 in 2014).

Under current law, if a parent at 200 percent of poverty gets a raise of a dollar an hour, raising annual income to $41,640, she hits the childcare cliff. The kids are no longer eligible for childcare aid. Monthly payments for childcare rise from $300 to $1,602 (an annual cost of $3,561 rises to $19,224). This parent needs a raise of $7.53 an hour to break even. This kind of raise -- about 38 percent -- is practically unheard of.

The governor’s proposal eases the cliff by gradually reducing subsidy until the family income reaches 300 percent of poverty – about $60,270 for a family of three using 2015 federal poverty guidelines. (Figure 1). This good move makes lives easier for families who have escaped poverty but still make too little to get by on their paycheck alone. The problem is, too few families ever make it to the cliff. It is too easy to fall through the cracks and get caught in the canyon.

Most fall through the cracks

State data tells us that less than 2 percent of families in the public childcare program ever make it to the cliff.[5] Most leave the program for other reasons before their income gets to that point. They fall through the cracks. These cracks include losing a job and not finding another one within allowed time; moving and missing a redetermination notice; providing incomplete documentation for eligibility; being short of the co-pay; or having kids who miss more than 31 days of care.

Caught in the canyon

Once out, a parent cannot get back into the program unless she takes a new job that meets the limit for initial eligibility. At present, the initial eligibility level of 125 percent of poverty is $24,732 a year for a parent with two children ($11.89 an hour for full-time work at 40 hours per week). The executive budget proposes increasing that to 130 percent of poverty, which would be $26,117 in 2015 ($12.55 an hour). Someone earning $27,000 will be above the level to qualify for initial eligibility. However, someone who started in the program at the very low level of initial eligibility and stayed enrolled in the program may be making much higher wages and getting assistance.

This seems like a strong incentive for someone to stick with one job as earnings rise - a fine ideal, but one that is hard to attain. As mentioned, program data shows that only one to two percent of program participants who left the program earned their way up to the cliff.

Conditions in the low-wage labor market can wreak havoc on eligibility. Stores reduce staff during slow periods, restaurants change employee hours, temporary jobs come and go. When a parent loses a job, she must find new work within a short time or lose her childcare aid. She has 90 days for the first time in a year that she must look for work and 31 days for subsequent times that year, in order to retain eligibility. If she misses the window and loses her childcare, she can get it back only by taking a job that pays no more than initial eligibility. The subsidy is so essential to her budget that this can trap her at bottom of the wage scale as she moves from one unstable job to the next in the churning, low-wage labor market.

Baby steps

The Kasich budget proposal for 2016-17 would ease the childcare “cliff,” which is the loss of childcare aid for a family at 200% of the poverty level (about $40,000 for a parent with two children). Instead of a sharp drop in assistance at 200 percent of poverty, the aid would taper off, ending at 300 percent of poverty ($60,270 for a family of three in 2015). This is a significant change but helps only a tiny share. There is a proposal to raise initial eligibility from 125 percent of poverty ($24,732 in 2014 for a parent with 2 children) to 130 percent ($26,117 in 2015). Co-pays for the families with income of less than the federal poverty level would be eliminated. The last proposal is very important. State data identifies inability to pay co-pays as one of the larger cracks in the program.

The executive budget also offers additional early learning slots for children of low-income families. According to testimony of Ohio Department of Education Superintendent Richard Ross, the budget proposes an additional $40 million over the biennium to serve an additional 6,125 children.[6]

This is a much-needed increase in investment. Education Week’s recent analysis of Ohio’s early learning programs gave the state a D+,[7] finding that in Ohio, almost a third fewer children from low-income homes (making less than $20,000 a year) get to go to preschool than those from homes making $100,000 or more.

Early learning slots for low-income children in the Ohio budget for FY 2014-15 were flawed. The new slots were for half days, but low-income families eligible for the program need full-day child care while parents are at work.[8] Quality early learning for children from low-income families is critical to boosting their opportunities – but it must also serve as childcare for working parents and their employers. The additional preschool opportunities proposed in this budget must be made full-day, or be merged with a public childcare program operating under parallel eligibility rules to give the child a consistent classroom, ensuring the stability needed to learn.

Recommendations

Lawmakers should craft a childcare fix that goes further than the governor’s proposals:

- Fill the cracks: Parents lose eligibility too easily. The largest categories for case closure in the public child-care program have to do with loss or lack of a job or qualifying activity. The labor market in low wage sectors churns, as described above. Another leading cause for termination is failure to provide verification of eligibility. People move, miss notices for documentation, and fall through the cracks. The public childcare program should accept children for a full year, regardless of what happens to the parent’s job or paperwork. If parents lose a job, the workforce system should help to find them another one, while their children stay in a stable environment. Other important programs, like affordable housing programs, work this way. Twelve months of consistent care offer long-term benefits for children. It will increase stability in the classroom, creating a better environment for learning.

- Eliminate the canyon: When a family falls through the cracks, they end up in the canyon. The parent must return to the level of initial eligibility to get childcare assistance back. Ohio’s initial eligibility - $11.89 an hour for a family of three at 125 percent of poverty – was among the lowest in 2014. The proposed changes would make it better, but still within the bottom 10 states (Table 1). Initial eligibility for public childcare should be 200 percent of poverty, as it was in Ohio six years ago and as it is in the ten states that have the most comprehensive approach. This would support families moving up the income scale and help them achieve stability in that climb out of poverty.

[1] Karen Schulman and Helen Blank, “Turning the Corner on State Childcare Assistance Policies 2014, National Women’s Law Center, http://bit.ly/1rnY5Av Note that Kentucky was the lowest, but raised initial eligibility to 140% of poverty in the middle of 2014.

[2] Child Care Manual Procedure Letter #77, February 27, 2014 http://bit.ly/1EJa8Qq

[3] “Parents and the High Cost of Childcare: 2013 Report,” Child Aware of America at http://bit.ly/1kt3Mv6

[4] Diana Pearce, “The Self-Sufficiency Standard for Ohio, 2013,” Center for Women’s Welfare, University of Washington School of Social Work, Prepared for the Ohio Association of Community Action Agencies, at http://www.selfsufficiencystandard.org/docs/OH13SSS_web.pdf

[5] E-mailed communication from the ODJFS office of Communications, April 10, 2014 and February 12, 2015. Forty-one percent of program separations in December 2014 fell into the category of “Automated case closure” or “immediate administrative closure,” but for the remaining 59 percent, there is a finely parsed classification of causes.

[6] Dr. Richard Ross, Testimony on K-12 Education 2016-17 Biennial Budget Priorities, Ohio General Assembly House Finance Committee, February 10 2015 at http://bit.ly/1w6STUh

[7] Catherine Candisky, “Ohio Schools Earn a “C” in Nationwide Review,” January 8, 2015 at http://bit.ly/1DpFttY

[8] Gongwer Ohio, “Senator Peggy Lehner to continue efforts to fund, overhaul early childhood programs, 11/6/2014 at http://www.gongwer-oh.com/programming/news.cfm?article_Cited in “A Budget that Works,” Policy Matters Ohio, January 29, 2015 at http://www.policymattersohio.org/budget-jan2015

Tags

2015Budget PolicyChild careRevenue & BudgetWendy PattonPhoto Gallery

1 of 22